What do you do when you lose? I mean lose hard. The kind of loss that leaves you doubled over and shaking. Think back to all the stories you know: a hero is wounded, defeated, or otherwise lost. He retreats, perhaps literally to a physical place like the forest or figuratively to a spiritual place of penance. There, he heals, consolidates his forces, regenerates. He leaves the retreat more powerful than he came. Finally, he returns to the place where he was first defeated, seeking victory. This a motif, a story arc that is fundamental to your culture. There is reason for this.

You need it.

You need this tale. Call it what you want. You probably know it as the “Hero’s Journey” but simply put, the stories you remember and hold on to show you a hero who retreats, regenerates, returns. They teach you how.

There are countless stories like this. The Count of Monte Cristo, for instance, gives you Edmond Dantès. He is a man wronged, cast down into darkness, imprisoned. He does not remain there. In the shadow, he learns, he trains, he prepares. He is not the same man who went in to prison. He is transformed, armed with knowledge and purpose. When he finally emerges, his enemies and society at large are not prepared for the sheer gravity, the overwhelming force of his return.

This is but one example. So many of your stories embody this arc, stories that you love, stories that speak to you because, at some level, you recognize yourself in them.

Life wounds you. The world, sooner or later, deals you a blow that you cannot shrug off. It leaves you picking up your teeth in the gutter. It humbles you. It will humble you. The question is never if you will suffer, but when and what you do after. Do you rot in defeat, or do you retreat, regenerate, and return?

The Retreat

There will be a time when you bite off more than you can chew. You will grow confident, overconfident, and advance your borders further than you are able to hold.

You are not exempt from this arc. No one is. Whether you like it or not, you are in the story already. Your forest, castle, or refuge might be a hospital bed. A season of obscurity. A job loss. A heartbreak. A year of quiet work with no recognition, no applause. That retreat is not the end however. It is not even a pause.

It is the forge.

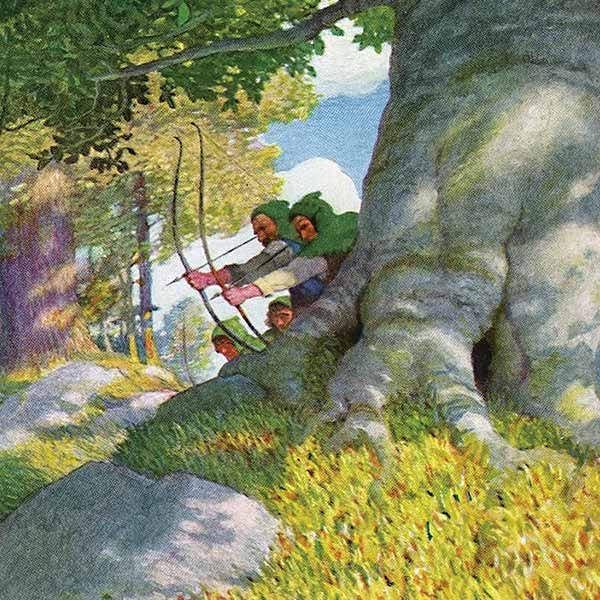

Consider Robin Hood. You know he steals from the rich and gives to the poor. You remember something about an archery competition and splitting arrows. In the original A Gest of Robyn Hode however, that competition to which bold Robin and his men merrily set off leads to an ambush that leaves Little John crippled and begging for death. He tells Robin Hood to cut off his head, to wound him so dire that their enemy won’t find him alive.

`Master,' then said Little John,

`If ever thou lovedest me,

And for that ilke lord's love

That died upon a tree,

`And for the medes of my service,

That I have served thee,

Let never the proud sheriff

Alive now find me.

`But take out thy brown sword,

And smite all off my head,

And give me wounds deep and wide;

No life on me be left.'

It is a low moment, likely the lowest in the Gest. Earlier in the story however, the company of heroes showed a sorrowful knight hospitality. He was down on his luck then but through their aid regains his lands and castle in which the ambushed heroes now seek shelter. There, in the shelter of Sir Richard’s hall, the story shifts.

`I would not that,' said Robin,

`John, that thou were slain,

For all the gold in merry England,

Though it lay now on a row.'

`God forbid,' said Little Much,

`That died on a tree,

That thou shouldest, Little John,

Part our company.'

Up he took him on his back,

And bare him well a mile;

Many a time he laid him down,

And shot another while.

Then was there a fair castle,

A little within the wood;

Double-ditched it was about,

And walled, by the rood.

And there dwelled that gentle knight,

Sir Richard at the Lee,

That Robin had lent his good,

Under the green-wood tree.

The retreat is met with kindness, with a hot meal, with resistance of further harm. The gentle knight raises his draw bridge and tells their pursuers to get lost. From this pause, strength returns. Little John heals, becoming “whole of the arrow” and the alliance between the outlaws of the forest and Sir Richard, the gentle knight, is only strengthened. Their retreat is dignified, even defiant. Note that it is not a passive hospitalization, but they take to the walls armed to win the day.

In he took good Robin,

And all his company:

`Welcome be thou, Robin Hood,

Welcome art thou to me;

`And much I thank thee of thy comfort,

And of thy courtesy,

And of thy great kindness,

Under the green-wood tree.

`I love no man in all this world

So much as I do thee;

For all the proud sheriff of Nottingham,

Right here shalt thou be.

`Shut the gates, and draw the bridge,

And let no man come in,

And arm you well, and make you ready,

And to the walls ye win.

`For one thing, Robin, I thee behote;

I swear by Saint Quintine,

These forty days thou wonnest with me,

To sup, eat, and dine.'

Boards were laid, and clothes were spread,

Readily and anon;

Robin Hood and his merry men

To meat did they go.

This is the gift of retreat; it gives you time to mend your wounds, yes, but more importantly it allows you to take stock of your resources and allies. If your life has led you to some inner Sir Richard’s castle, some place of quiet and repair, you must not be ashamed; you must take to the battlements with a keen eye and bow in hand. Robin Hood’s men earned their retreat through the grace of hospitality earlier in the story. Remember that wherever or whatever your retreat looks like, you have earned it too. It is yours to use, and you need to use it. Knock on the gates. Call in the favor.

The Regeneration

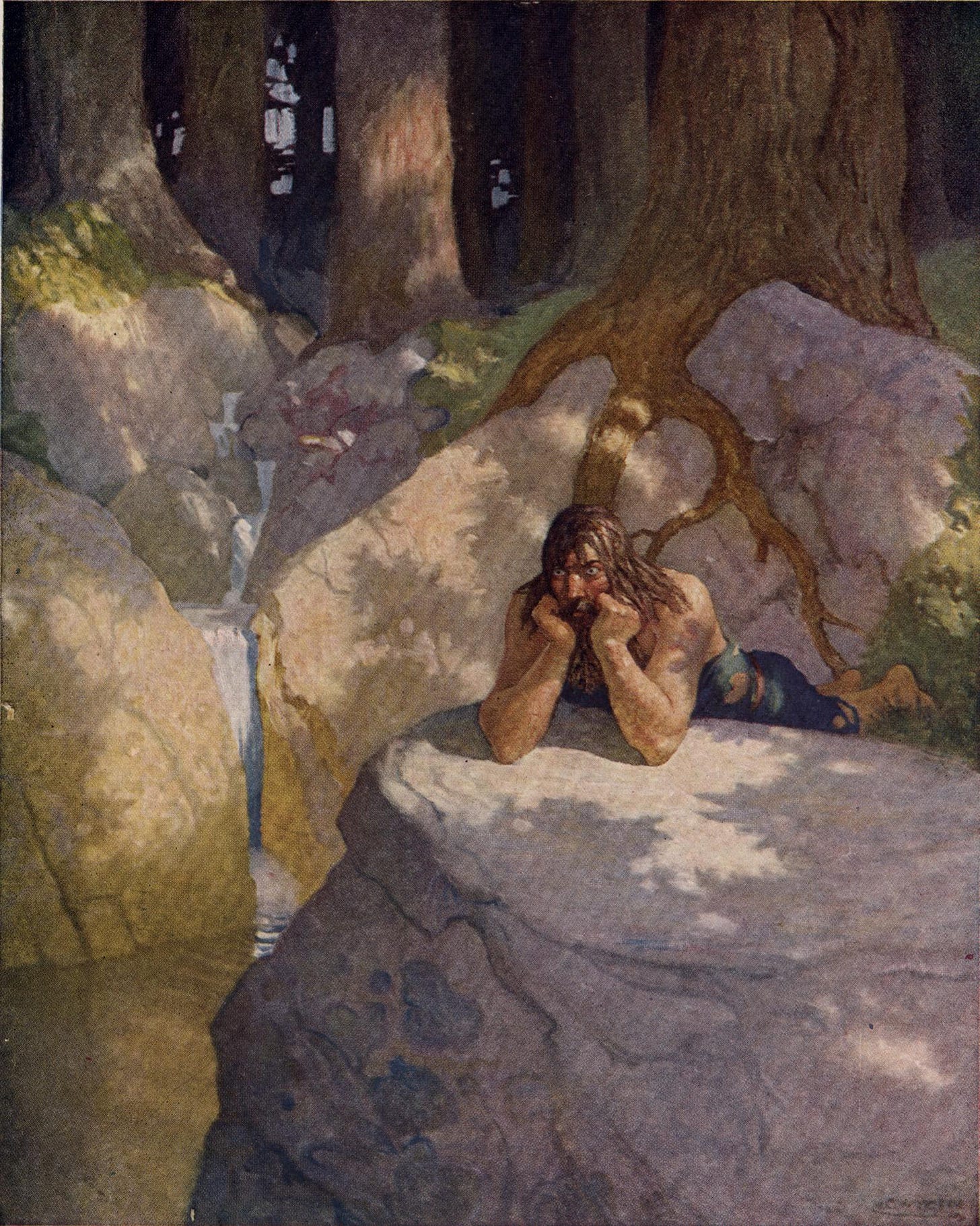

These stories happen time and time again. Consider Lancelot in the end of Le Morte d’Arthur. He has retreated to the wilderness with a small band of his fellow knights following his sin that has fractured the Round Table and left Arthur’s kingdom in shambles. His shame burns and he vanishes into the wilderness.

There, he lives as a hermit. No horse, no armor, no hall. He lives simply. He prays in silence, his comforts are cold streams and coarse bread. He does not speak his name. He does not touch his sword. There are no trumpets in this season, no banners, no garlands. There is only the slow, hard grind of repentance. Lancelot sheds the grandeur of chivalric romance and goes to war only with himself.

That is regeneration.

Lancelot’s redemption arc begins when he stops trying to wield power and instead lays it down. You will reach a point in your life where the old tools no longer work, when your sword no longer strikes true, when the charm wears thin, when the armor’s burnished gleam rusts, when the garlands wilt.

That is the moment when you go to ground and begin the work.

There, in the wilderness, something happens. Slowly, painfully, he is changed. He grows lean. He learns to weep, learns to pray, learns to wait.

This is what redeems him.

He fasted until he grew lean, rang the bell for matins, swept the floor, studied the Psalms. His companions, one by one, found him, and seeing the change, were changed themselves. They too took the habit. They too renounced the world. What the Round Table had begun in glory, this quiet brotherhood completed in repentance.

We discussed how Little John’s wound was mended. Lancelot was not so much mended as remade. His sorrow was not alleviated, if anything it became more extreme and was the ground in which his holiness took root. He buries Guinevere with prayers and incense, singing the mass with trembling lips not as her lover but as her priest.

This was his final quest: not the Grail, not glory, not another dragon. Just the slow, aching work of sanctification.

After you retreat into the wilderness, after you begin regeneration, you do not reclaim what you had. You make something better. Not a return to what was, but a preparation for what can be. Lancelot does not receive absolution and returns to knighthood; he transforms and becomes worthy of peace, of holiness, of heaven.

Your own regeneration may not be so dramatic. Perhaps your retreat looks like cutting out a project for which you do not have time. In such a case, your regeneration focuses not on gaining the time you need, but rather refocusing on what you need to be spending the time you have. In some small way, you reform yourself. Perhaps that is as simple as refocusing on what matters, on what you can actually achieve.

Author’s Note: This essay is not just about stories from long ago or characters out of myth and fiction. It’s about learning how to retreat with dignity, to regenerate with purpose, to return with keen judgement. It is about how to face real loss.

I’ll show you how we’re applying this arc to a recent, heartbreaking setback right here in our own little meadow so you have one more arrow in your quiver when facing your own. That is ultimately what these Reports from the High Wood provide: grounded lessons for thriving in a wounded world. If this resonates with you, if lessons hard-won in dirt and work mean something, please consider subscribing.

The Return

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Echoes from an Old Hollow Tree to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.